Degenerative disc disease is another form of arthritis of the spine.

Degenerative disc disease is another form of arthritis of the spine.

Degenerative disc disease is often described as a “wear and tear” condition. For reasons not fully known, possibly partly due to ageing, the water content of the disc between the back bones reduces over a period of time. This can be detected on MRI scanning and is generally regarded as being related to a wear process in combination with ageing. At some point, again for reasons which are poorly understood, this process may give rise to pain within the disc and therefore in the lower back. Pain related to a disc may radiate to the buttocks and into the back of the legs also.

Typically, pain related to a disc in the lower back is made worse by sitting rather than standing and may also be heightened by coughing, sneezing or straining. Any activity involving forward bending may also bring on or worsen the pain. Although the cause for the pain specifically is not well understood, much research is currently in progress on this subject, and it seems that, at least in part, an inflammatory process involving irritative proteins in the region may perpetuate the problem.

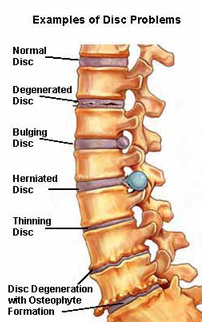

The outer edge of the disc is a ring of gristle-like cartilage called the annulus. The centre of the disc is a gel-like substance called the nucleus. Discs have a high water content. As people age the water content decreases, so the disc begins to shrink and the spaces between the vertebrae get narrower. Also, the disc itself becomes less flexible.

Other conditions that can weaken the disc include:

- The fibrous outer ring may crack or tear

- Sometimes fragments of the disc enter the spinal canal where they can damage the nerves that control bowel and urinary functions

Pain from a disc may give rise to protective spasm of the lower back muscles which may contribute to the symptoms. The process of wear is a slow one, initially obvious with heavy work or strenuous exercise and commonly only present from time to time. Symptoms of wear in the spine tend to wax and wane over a very long period, often arising for no particular reason and falling away again similarly. Very few people suffer constant pain on a daily basis without “good days and bad days”.

Treatment, where possible, is often determined by the degree of pain and its constancy as well as the level of difficulty in undertaking normal daily activities and effect on quality of life. In the vast majority of cases, the onset of back pain from any specific event is likely to eventually subside although this may take many months.

Symptoms

Symptoms of degenerative disc disease can include pain in the involved areas of the spine and, in some instances, pain or numbness to the arms or legs. Loss of flexibility is also typical. Although the problem may reside in the disc between the vertebrae, pain is commonly referred to the region of the buttocks or, in some instances, down the back of the thighs. Referred pain from the disc itself rarely goes below the level of the knee in the absence of a pinched nerve.

Typically discal pain is more severe with coughing, sneezing or forward bending of the spine and in sitting, particularly for long distances such as car or plane travel. Typically the pain increases over the course of the day and tends to be worse with heavy physical activity or sports.

Treatment Options

For most people, degenerative disc disease can be successfully treated with conservative care. Most patients will experience low-grade continuous but tolerable pain that will occasionally flare (intensify). The frequency and intensity of the flares can be managed with an exercise program. The best manner in which to manage long term tolerable lower back pain is hotly debated. Exercises vary in their aims however there is a reasonable body of evidence to suggest that overall aerobic fitness programs aimed at increasing general cardiovascular fitness are as effective as more specific exercise regimes for the muscles of the lower back and abdomen.

Although it may be unexpected, in the long term people with degenerative disc pain benefit most from increased physical activity, not rest. This seems hard to understand when, for example, an injury to the knee needs rest and gradual increase in activity. In the lumbar spine the improvements in general fitness and weight control which stem from regular activity of any kind seem to be protective against relapses of chronic back pain. Even when back pain has flared up acutely, the best results are obtained from an early return to physical activity, including work. These and other principles are employed in back rehabilitation programs.

Recognising symptoms

Low back pain affects at least four out of five people and its causes are many. So pain alone is not enough to localise the pain to a disc problem. However, if the back pain is the result of a fall or a blow to your back, do not hesitate to contact a doctor.